News Team member Ananya Dash delves into the rising popularity of skincare among today's teens and tweens due to social media, the risks it poses, and expert guidance for this group going forward.

A New Frontier in Treating Depression and Gut Health

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation may help illuminate the complex interplay between gut health and mental well-being.

By Katie Stachowicz

In September 2018, a 53-year-old woman walked into a Swiss clinic. She had been living with major depressive disorder all her life. Despite rotating therapists, several different medications, and two hospitalizations throughout her life, her depression was not getting any better. At the same time, she suffered from severe constipation, and strict diets, nutritionists, and enemas did not help. She was there to opt for a novel treatment known as Fecal Microbiota Transplantation, or FMT. And as her clinical team later described in the journal Frontiers in Psychiatry, the treatment for her gut disorder had an unexpected effect on her state of mind.

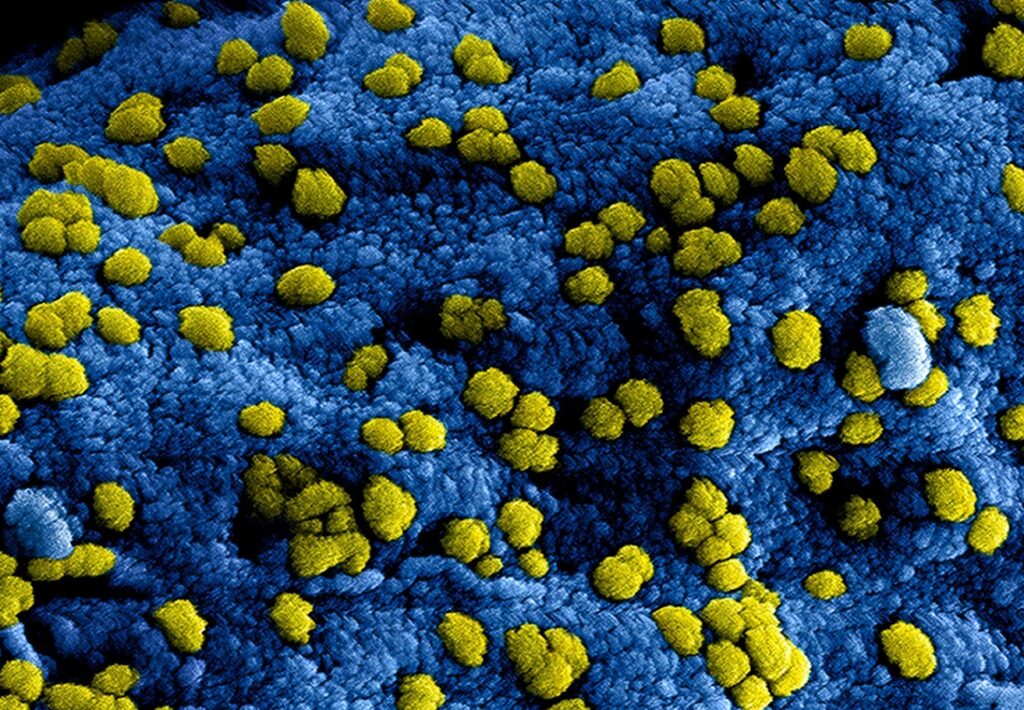

FMT is what it sounds like: treatments created from the feces of healthy donors. While it may sound gross, what comes out of our bodies mirrors what is going on inside our gut. Millions of bacteria live in our intestines, and these bacteria are critical to our health, despite being foreign organisms, not human cells. They help us digest and process the nutrients we consume before our bodies shuttle those nutrients to other organs and systems.

This bacterial community is present on a smaller scale in our poop. Special techniques allow scientists to screen samples for anything that might be harmful and isolate the healthy gut bacteria. They can then turn these bacteria into pills or another form of medication. Introducing gut bacteria from a healthy donor to a patient has been successful for gastrointestinal problems, but using it for psychiatric disorders is a newer endeavor. How well it works remains to be seen

“FMT [for psychiatric disorders] is a very interesting therapy,” says Mireia Valles-Colomer, an associate professor and researcher at University Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, Spain. She heads the institution’s Microbiome Research Group. “Administering bacteria that we have low levels of can work surprisingly well.”

Research spanning several decades has confirmed that our gut and our brain communicate constantly. Even beyond that, they can influence each other, perhaps even so much that not having the right support system of bacteria in the gut can lead to sustained, severe depression.

While researchers have known for years that the diverse gut ecosystem influences the brain, how exactly it does that remains a puzzle. How to use that knowledge to treat patients remains equally as elusive.

The gut microbiome

The human gut, or gastrointestinal system, includes the stomach, intestines, and colon. In addition to dozens of specialized human cell types that help contain stomach acid, transport nutrients, and filter out waste, the gut contains millions of bacteria, archaea, and other single-celled life forms. These organisms are not here to cause disease – in fact, we need them to properly maintain our body functions. This group of microorganisms is called the gut microbiome.

The gut microbiome is home to hundreds of species of our single-celled friends, who help us out with everything from breaking down complicated molecules into smaller building blocks to maintaining the mucus lining of the gut (which helps us not get dissolved by our stomach acid). While the exact makeup varies a lot from person to person, some groups seem pretty important for maintaining a healthy gut, including high levels of Akkermansia and Faecalibacterium and low levels of Bacteroides and Campylobacter. Importantly, though, the exact species and number seem less important than the overall picture of the environment. There is no one “right” gut microbiome.

“There are lots of different microorganisms in your gut,” says Brittany Butts, an associate professor and researcher at Emory University School of Nursing. “And diversity is important. Just like how in the real world you don’t want everything to be the same, you want a wide variety of microbes in your gut.”

The gut and the brain are connected by a bidirectional highway known as the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve allows the gut to talk straight to the brain and vice versa, allowing for fast and efficient communication. The gut “talks” through the molecules it churns out, from short-chain fatty acids like acetate and butyrate to neurotransmitters themselves like serotonin and norepinephrine. These products can relay information about the gut’s condition to the vagus nerve or be transported directly to the brain.

“There is no gut-brain communication without the microbiome,” says Valles-Colomer. “It produces all these molecules similar to those produced in the brain, compounds that signal to neurons.”

Think of the gut as a city and the microbiome as all its citizens. If everything is going well, people are getting what they need, and everyone is happy, it is unlikely that there will be mass upsets and riots. However, if whole populations stop getting what they need to thrive, or one group starts stealing resources from others, there will be some upset, and eventually, someone is going to complain to the mayor (in our case: the brain). If the mayor does not take quick action, things get worse, fast, and often exponentially harder to fix.

The big takeaway here is that it is not just the brain that influences the gut. Through its actions, the gut also influences the brain.

The gut microbiome and diet

Unsurprisingly, diet has a big influence on our gut microbiome health. Beyond just providing proper nutrients for our health, what we put into our bodies can affect which microbiotic species live and die, which can then go on to affect our mental health.

“The microbiome is a living entity,” notes Brittany Verras, the Associate Director of Nutrition at Emory University Student Health and a registered dietician, “and what we consume is both feeding and propagating them. [We have] power to help them thrive or crowd them out.”

Western diets are high in saturated fats and sugars, all those good fried foods and sugary snacks we love to indulge in. Unfortunately, these cheat-day snacks are not great for the gut microbiome or the brain. They can alter microbiota diversity, leading to reduced intake of nutrients essential for body health.

One research group showed that mice on a high-fructose diet developed inflammation in their hippocampus, an area necessary for many types of learning and memory, and that this inflammation was related to an imbalance of the gut microbiome. Adding in some products of the microbiome – specifically, those short-chain fatty acids mentioned earlier – helped reduce brain inflammation and rebalance the gut.

Additionally, a 2009 study in the British Journal of Psychiatry found that avoiding high-fat and highly processed foods may lower the risk of depression. Researchers identified two primary dietary patterns in a group of over 3000 white European middle-aged participants: primarily “whole food” (characterized by lots of fish, vegetables, and fruit) and primarily “processed food” (characterized by sweetened desserts, fried food, and processed meats, among other things). They then studied the association with self-reported depression scores five years later, controlling for factors like smoking and socioeconomic status. They discovered that subjects on primarily whole food diets on average had fewer depressive symptoms after five years, while patients that consumed lots of processed foods had more.

There are limitations to the 2009 study, the primary one being that they excluded Black and Asian patients due to notable differences in eating patterns, but it points towards a familiar conclusion: diets that rely on processed foods may increase the risk for mental health concerns.

This doesn’t mean you shouldn’t indulge in a donut or Twinkie. As Butts said, diversity in your gut is key, and to feed a diverse population of bacteria, you need a diverse diet. Some processed or fried treats are not going to hurt you as long as they are not the base of your food intake.

A 2012 study in an Irish nursing home famously found results that pointed towards a similar conclusion. Frailer residents received bland, easy-to-digest food, which reduced the diversity of their gut microbiome compared to residents who followed a more varied diet.

Research over decades shows that diets with lots of whole grains, vegetables, fruits, and lower-fat dairy, such as the Mediterranean diet, promote microbiota diversity in the gut. They also lower unnecessary inflammation and are associated with decreased risks of depression.

A 2017 research study from Australia recruited patients who demonstrated high levels of depression and a nutrient-low diet. One group had multiple sessions with a clinical dietician to receive advice on how to improve their diet; the other group went about their daily lives without intervention. Controlling for those who received outside treatments such as therapy and/or medications, individuals who met with a clinical dietician had significantly improved depression symptoms after just 12 weeks.

Scientists are still working to figure out whether this association is causal — if a varied diet diversifies the gut microbiome, which protects against mental health disorders, or if a varied diet diversifies the gut microbiome and, through a different mechanism, protects against mental health disorders.

A stressed gut

Being stressed has a variety of non-brain effects, of course. The heart beats faster; adrenaline floods the bloodstream; and breathing speeds up. Short-term stress can be a good thing. It improves memory, boosts the immune system, and increases motivation to reach goals. Long-term stress, though, takes a toll on every part of the body, including the gut microbiome.

Gut bacteria wear a lot of hats. “The gut microbiome plays a large role in modulating different immune system compounds,” says Valles-Colomer. “Many of these are anti-inflammatory.”

Scientists have known for years that chronic stress increases inflammation and that inflammation can affect the bacteria species present in your gut. While we’ve mostly been focusing on their direct effect on mental health, many species play a huge part in boosting the immune system, and research shows that as stress increases, certain health-promoting bacteria in the gut decrease. Inflammation can also lead to a “leaky gut”, where the barrier that keeps the bacteria in the gut breaks down and allows them to cross into the bloodstream. This triggers the immune system to fight back against what it thinks are foreign invaders, and since inflammation is an immune response, the cycle only gets worse.

However, this is a two-way street. Stress can change the microbiome, and natural variability in the gut microbiome can affect how different individuals respond to stress. A 2019 study published in Nature, one of the highest-reputation science journals, looked at natural differences between healthy male rats in a chronically stressful situation. Rats who seemed to just “give up” and accept their situation had a markedly different gut microbiome composition than rats that were naturally more resilient to stress.

A study out of Ireland published a few years earlier found that replacing a healthy rat’s gut microbiome with depression-associated microbiota from patients diagnosed with depression increased depression-like symptoms in the rats. They were more anxious and had a harder time metabolizing a precursor to serotonin, a neurotransmitter that is strongly linked to feelings of happiness and reward motivation.

It is important to keep in mind that animal studies often can not be directly translated into humans. However, the idea of the “bidirectional highway” keeps popping back up. If administering gut bacteria from a depressed patient can increase depressive symptoms in a healthy animal, it seems possible that giving bacteria from a healthy patient could decrease depressive symptoms in a depressed animal.

Balance the gut, balance the brain?

FMT is typically used to combat antibiotic-resistant gastrointestinal infections such as Clostridium difficile. Within the past few years, clinicians and researchers working on gut-brain research came up with the idea to use it to treat medication and therapy-resistant mental health disorders. So far, it has had varying results. A few small studies, including the one in Switzerland, have found mild improvement in mood symptoms in patients who have coexisting and otherwise untreatable gastrointestinal and mental health diagnoses. The risk, though, may outweigh the reward.

“[FMT] has some beneficial effects,” said Butts, “But sometimes it can make things worse. There are so few studies that it’s overall unclear.”

Valles-Colomer added, “There are very few cases where it has worked well. It might work, but there just isn’t enough information yet.”

The question of whether changing what is in the microbiome can change mental health remains. There is some promising evidence that introducing a “healthy” gut microbiome to an unhealthy individual can change how they think. Take our Swiss woman she and another patient who opted for this treatment both exhibited marked improvements in their depression after just a few weeks. However, these effects might not be long-lasting – between four and eight weeks, their symptoms worsened again, with one patient exhibiting similar symptoms to before treatment.

More research needs to be done into how to use this “two-way highway” to help treat mental health disorders. Few think that FMT is the “next big thing” in mental health treatment. Many, like Verras and Butts, argue that changing lifestyle and diet will go further to keep the microbiome healthy than a single medical treatment. Others, like Valles-Colomer, think that an approach of administering specific compounds like butyrate holds more promise than FMT.

FMT may not be a cure-all for every treatment-resistant psychiatric disorder, but one thing is clear: there is an important connection between the gut microbiome and mental health. Ensuring that we support the ecosystem in our gut may go a long way toward supporting ourselves as well.