News Team member Caroline Hansen reports that hospital closures across the United States threaten equitable healthcare access for rural populations and demand solutions.

The Dimming Light of Medicine

Fatigue and disillusionment in the face of an overburdened healthcare system are a growing crisis among American physicians.

By Lexy Campbell

One physician confesses he dreams of the day he can resign. Another has been working for nine days with no break, stacking up six scheduled regular work days, two days on call, and one emergency surgery. A third feels that he can no longer truly focus on his patients, given the demands of administrative meetings and hours filling out electronic charts, When he finally gets off-shift, he drives home and crashes into bed, knowing it will be just a few hours til he must get up and do it all again.

These disclosures — made by working physicians in Tiktok videos, Youtube confessionals, podcasts and essays — capture the real-world stress experienced by American physicians. They are burning out. The American Medical Association reports that nearly 6 out of 10 physicians report some signs of burnout, and nearly 5 out of 10 physicians are experiencing high levels of stress, and the system within which they work is to blame.

“While burnout manifests in individuals, it originates in systems,” says Christine Sinsky, MD, the AMA’s vice president of professional satisfaction. “Burnout is not the result of a deficiency in resiliency among physicians; rather, it is due to the systems in which physicians work.”

Furthermore, several sources express concern for an impending physician shortage in the United States, which would further stress the healthcare system. The Association of American Medical Colleges, a nonprofit association that serves more than 158 medical schools and 400 academic health systems, predicts that there will be a physician shortage of 124,000 physicians by 2034. The COVID-19 pandemic gave the first glimpse of the vulnerabilities of a stretched-thin healthcare system. The worsening quality of patient care, physician burnout, and increased physician turnover were only a few of the effects observed during staffing issues during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The complex sources of physician shortages

The American physician shortage is a complex problem that is only partially reliant on the number of physicians present in the United States or will be present in the next ten years. “When we ask, How would we know that a physician shortage exists, there are a lot of things that you might point to,” says Bryan Carmody, a pediatric nephrologist and associate professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School. “But if you think about those things a little, the problem is not too few physicians. Physicians do not have the incentives to practice in the ways that we want them to practice.”

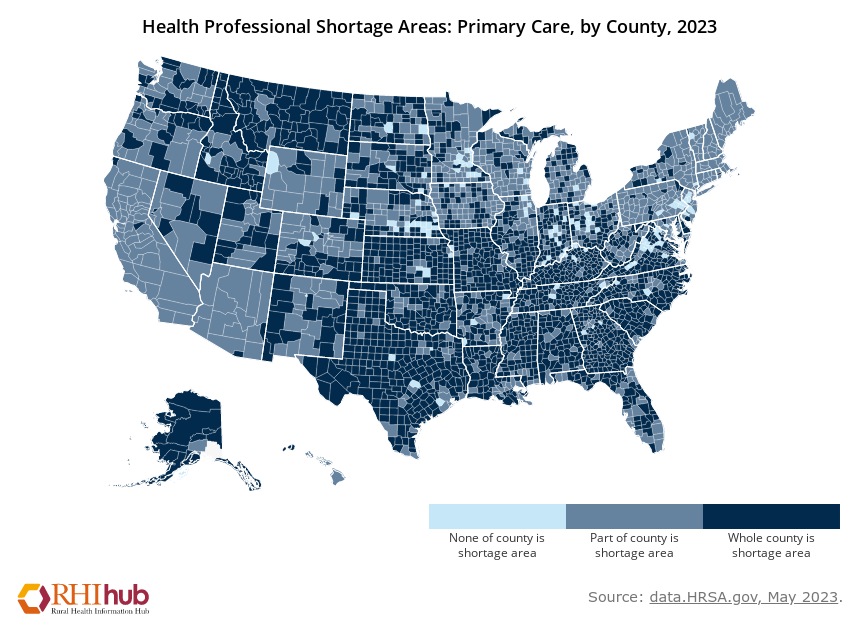

The seeming physician shortage is not due purely to the lack of available doctors. Physicians are not incentivized to provide care in all areas, such as rural or low-income regions, creating an imbalance of doctors. Therefore, some regions in the United States have doctor shortages, whereas others do not.

With each year that the American medical system does not address the underlying problems beneath the imbalance and shortage of doctors, the vulnerabilities of the healthcare system will closely parallel that of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A dwindling medical workforce

The sources of the problem are known. America’s population is aging: Over the next 15 years, the proportion of people over 65 is predicted to grow by 42%, and the proportion of those over 75 is expected to grow by 74%. As we age, we require more healthcare and assistance. Our bodies move slower, and our risk of diseases rises.

As the American population grows older, so do the current practicing physicians. A report from the Association of American Medical Colleges estimates that within the next ten years, more than 2 out of every 5 physicians will be older than 65, the age of retirement. Because of the aging population, the Association of American Medical Colleges predicts this is one reason we will face an extreme physician shortage in the United States within the next ten years.

Physicians who remain at work will be reducing their hours. A 2020 paper published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings found that 40.3% of clinicians said they would reduce their work hours in the next 12 months. This is double the number of doctors who planned to reduce their hours 10 years ago. With reduced hours, a physician can see fewer patients, resulting in a shortage of doctors.

The likely cause for physicians choosing to reduce their hours is burnout. “They [burnout and physician turnover] are very closely related. When you have people that are not happy doing what they do, they are not doing it any longer than they must,” said Scott Yates, MD, founder and president of the Center for Executive Medicine in Texas. Additionally, burnout decreases the rate of productivity so, physicians see fewer patients.

Physician burnout is like burnout in any other field: a sense of mental, physical, and emotional exhaustion. Physician burnout results in physicians feeling less satisfied in their personal and professional lives. According to the study published in Elsevier, about one-half of American physicians experience burnout. Burnout is associated with an increased risk of medical errors – with medical errors doubling when a physician faces burnout. “A burned-out doctor is dangerous. As humans, we are better when we are happy, we do better, we perform better,” said Yates.

Not only is physician burnout dangerous for patients, it is dangerous for doctors. Burnout has physical, emotional, and psychological effects. Studies find that physician burnout is associated with depression, substance abuse, and poor cardiovascular health. Burnout, like any other form of prolonged stress, is dangerous for the body and can result in long-term health effects.

To address burnout, one must know the sources of stress that cause burnout in physicians. Unfortunately, short-term fixes, such as meditation courses, are often used instead of addressing the underlying problems that result in burnout. Several areas of the modern-day healthcare system put a strain on physicians.

Caring for paperwork, not patients

At the forefront of these stressors is the electronic health record (EHR), a tedious electronic health charting system, and the complicated American insurance system. “Burnout is not a physician-centered issue. This is victim blaming. The system is terrible; the EHR [electronic health record] is awful. And you are telling doctors to buck up. It is a big issue and an ongoing one with a lot of misunderstanding,” Yates says.

Physicians spend about 35% of their time documenting in EHRs. Writing in the EHR serves two purposes: to track patient data over time and to track services for billing and payment from insurance to physician. “The fundamental problem is almost unique to healthcare… the consumer is not the customer. The customer is the health insurance,” said Yates. In the ideal world, physicians’ customers would be patients, not insurance companies. However, since the customer is health insurance, physicians must balance prioritizing doing their ethical job to care for patients and writing their every step in the electronic health record so they can be paid for their labor.

In addition to the aging population, burnout, and stressors, such as the EHR and the American insurance system, a maldistribution of doctors results in shortages in some areas in the United States. Prices in medicine are not set by supply and demand. For example, this means the price of seeing a single pediatrician in a small rural Georgia town is the same price of seeing one of a hundred pediatricians in Atlanta, Georgia. Although there is more demand for a pediatrician in the small rural town, the price they can charge is the same or less due to the lower cost of living. “You get what you get depending on what the payer will pay, regardless of where you live. There is no mechanism for hospitals to pay more to lure people into rural areas,” said Carmody while discussing his 2020 physician shortage paper in PubMed.

Finding ways to keep physicians working

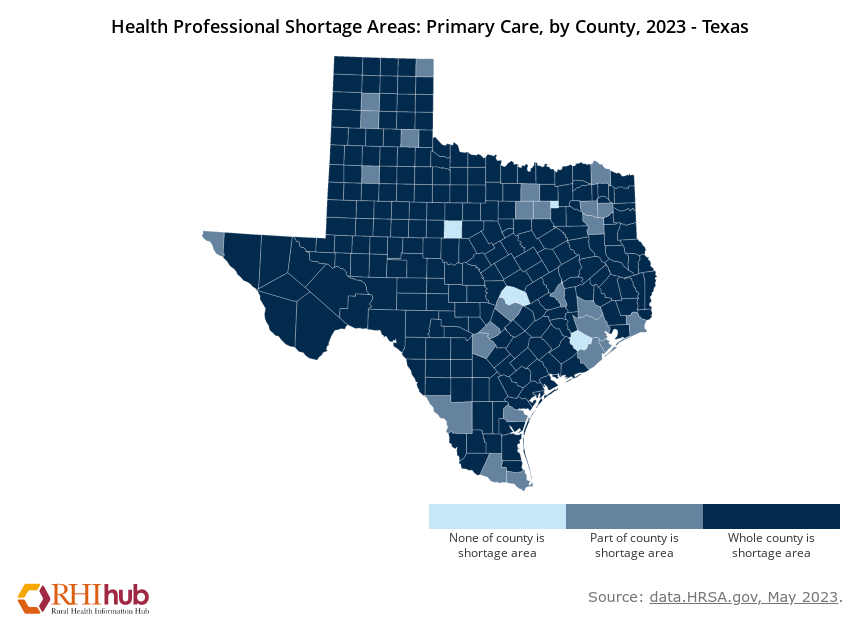

A 2023 paper in the Journal of General Internal Medicine examines incentives and programs to overcome the rural physician shortages in the United States. The rural physician shortage affects the health of nearly 50 million Americans. In areas most affected by the shortage, residents are sicker and have a higher mortality rate in comparison to areas that have sufficient doctors. The paper found that the Southeast and Midwest have the most doctor shortages; however, these areas have the most programs dedicated to drawing doctors into these areas.

Ninety percent of incentive programs are short-term recruitment programs designed to recruit doctors for one to nine years rather than have them stay. Unsurprisingly, the paper found the most common incentives were financial, like loan repayment programs. “Human beings respond to incentives, economic mainly,” said Carmody when asked about ways to redistribute doctors. Incentive programs, such as the J-1 Visa Waiver program, programs for sponsoring international doctors, and scholar programs for medical students or physicians were also common.

Physician retention programs — programs dedicated to incentivizing physicians to move and stay — are uncommon. The paper found that only 10% of incentive programs present in the United States targeted physician retention. “While many recruitment programs exist, very few have elements of or focus on retention,” said Kelley Arredondo, assistant professor at the Baylor College of Medicine. “We need to provide rural physicians with continued support, tools, training, and mentoring once they are in rural areas to enhance their work-life balance and professional development.”

Although several rural incentive programs exist, more are needed. For example, Texas desperately needs more incentive programs because it has one of the highest reported rural doctor shortages. Additionally, as new physician incentive programs are implemented across the United States, studies need to be conducted to track their effectiveness. “It is unclear how effective current recruitment and retention programs are and we need to better understand their efficacy,” said Arredondo. Understanding which programs are more effective and which are not will help States allocate funds to programs that will have the greatest outcomes for physicians and patients in physician-shortage regions.

Imagining a sustainable workforce

A 2020 paper published in PubMed found that expanding graduate medical education programs could be beneficial to addressing physician shortages in the United States. The paper found that there is a shortage of physicians but not a shortage of doctors. Physicians and doctors are not the same. Doctors become licensed physicians through residency training. Without residency, doctors cannot practice medicine or become licensed physicians. The paper estimates that over 4,000 Americans graduate as doctors but cannot obtain residency training, so they cannot work as licensed physicians.This problem can be attributed to the need for more resident physician jobs.

On April 27, 2023, U.S senators Bob Mendez (D-N.J.), John Boozman (R-Ark), Susan Collins (R-Maine), and majority leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y) announced the re-introduction of the bipartisan Resident Physician Shortage Reduction Act. This legislation would lift the cap on the number of Medicare-graduate medical education (GME) positions, resident physician jobs, and gradually raise the number of resident medical positions to 14,000 over the next seven years.

Programs focused on expanding graduate medical education, physician retention, and recruitment are integral to addressing physician shortages in the United States. Dr. Doe’s familiar narrative and examination of the potential causes behind a physician shortage underscore the need for systemic change. Only by addressing the root causes and fostering a supportive environment can we pave the way for a healthcare system where physicians, such as those tellling their stories on social media, can rediscover the joy of their profession. Addressing physician shortages in the United States will ensure that physicians can provide quality care to all Americans while not losing themselves to the profession.