News Team member Stephanie Oehler describes how the online "trad-wife" aesthetic fuels the flames of the anti-vaccination movement during the second-largest measles outbreak of the 21st century.

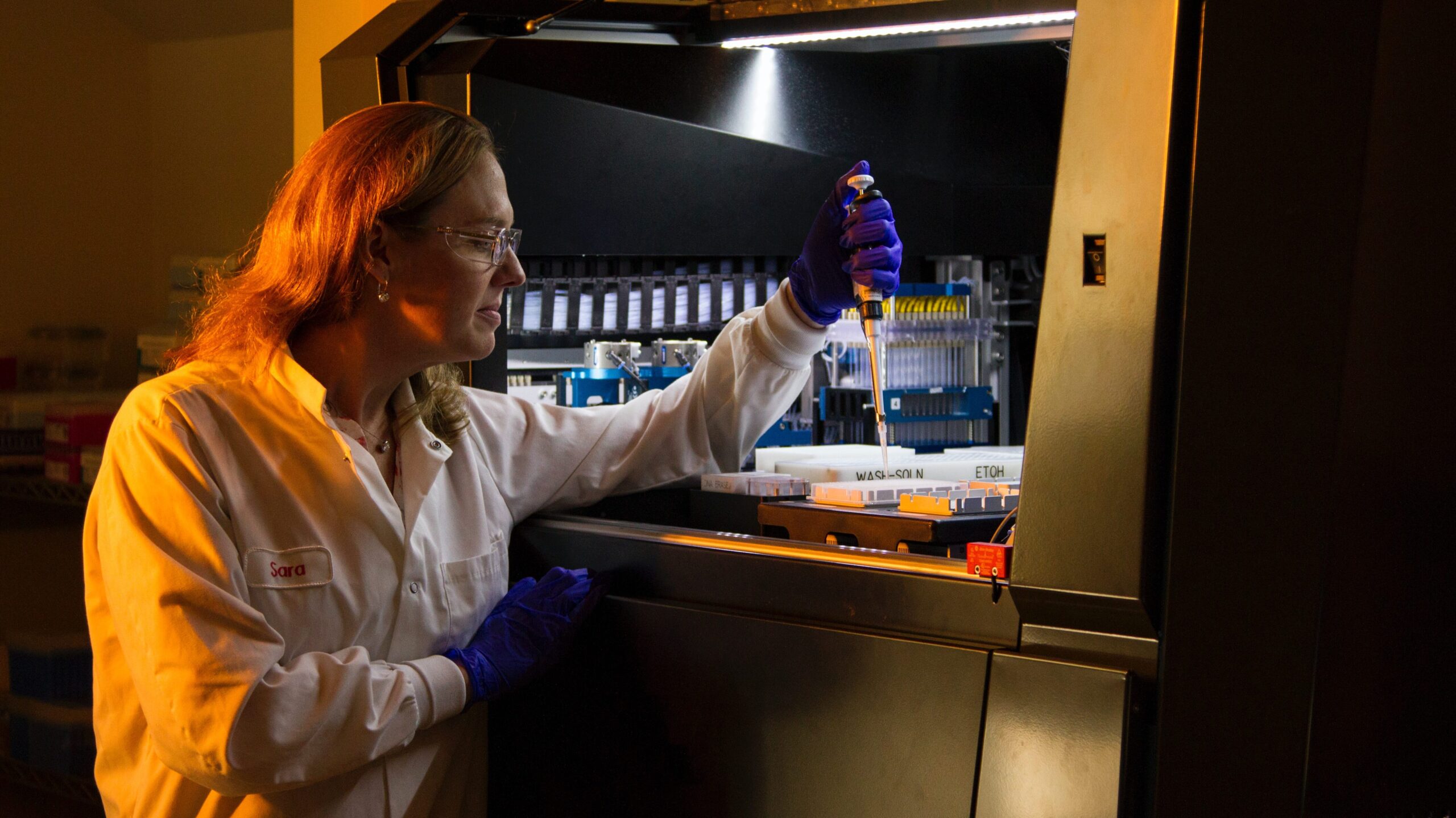

Emory’s JScreen Study Delivers Comprehensive At-Home Testing for Genetic Risks

Studies show using telehealth for cancer-risk evaluations solves access problems and increases community comfort

By Madison Woods

Almost 10 years ago, researchers at Emory University became concerned that genetic testing might not be accessible and affordable for disadvantaged populations. With that concern in mind, they started a program called JScreen that has changed the lives of many. The idea of using telehealth services to provide genetic counseling was innovative and transforming.

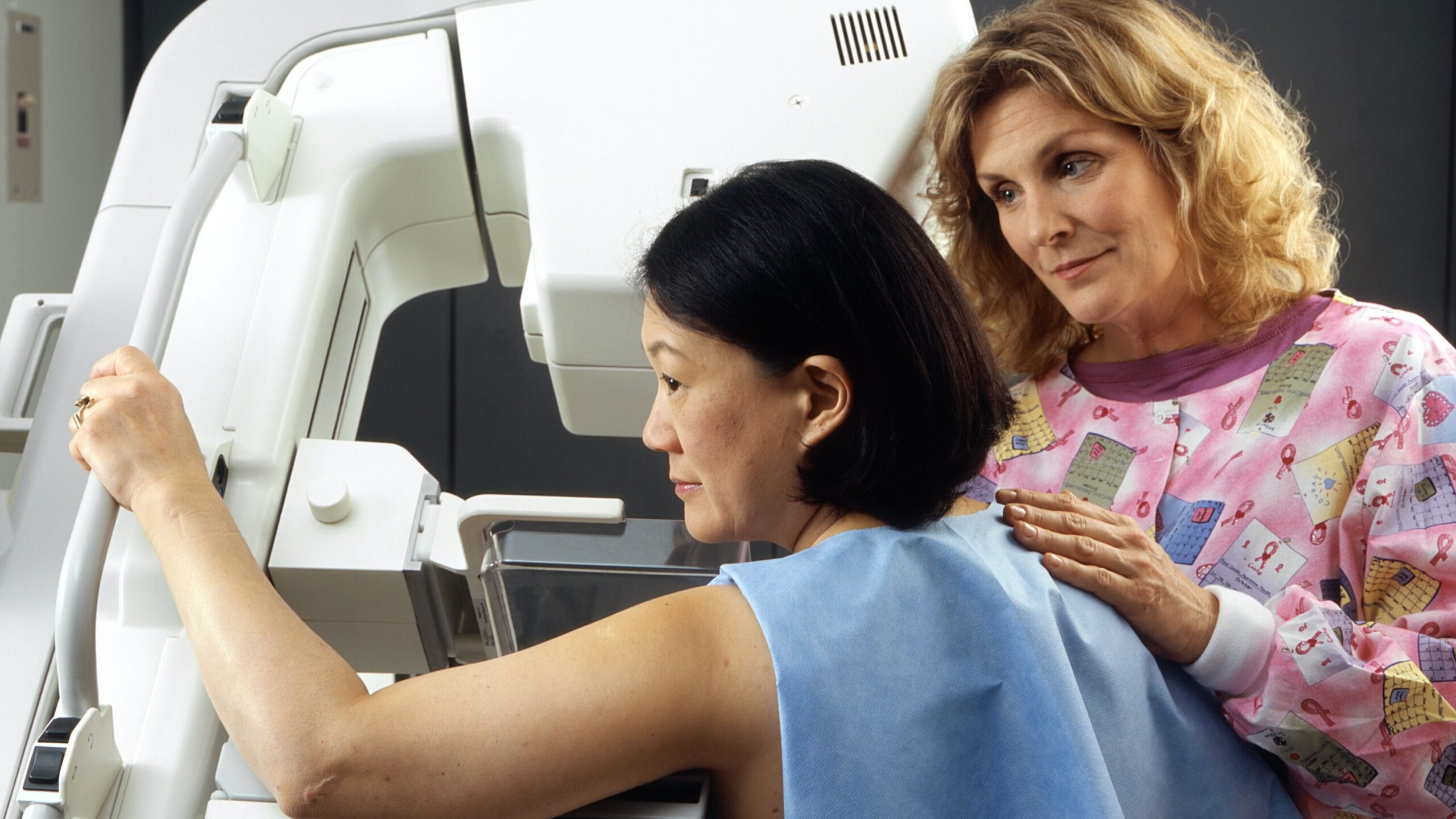

Most people have likely known someone in their lifetime who was diagnosed with breast cancer. It is a concern for men and women of all nationalities, but it is one of utmost concern for those of Jewish heritage. Studies have shown that Ashkenazi Jewish individuals are at a 1 in 40 risk of having a BRCA mutation that may lead to breast cancer — 10 times the risk experienced by the general population. Responding to that alarming statistic, the team behind JScreen launched the PEACH BRCA Study, with the goal of creating a constructive model for BRCA testing in those Ashkenazi Jewish individuals who might not meet average national testing criteria. This genetic screening program offers at-home saliva testing for more than 60 cancer genes, with disease response and education included, allowing large populations to take action to prevent cancer or detect it in the early stages.

“Other healthcare providers have been using ‘traditional’ methods of counseling and testing patients that have been very successful for some people, but may have missed positive results in other people,” says Melanie Hardy, director of genetic counseling services for the JScreen project. “For the PEACH BRCA study, we knew that it would be hugely impactful to bring affordable, accessible testing to people across the country, long before we ever formulated a plan to make it happen.”

In July of 2019, 501 members of the metro Atlanta Ashkenazi Jewish community participated in a study in which they completed questionnaires and then were offered genetic testing to screen for the BRCA gene. Analysis of the responses showed that not a high percentage carried cancer genes; however, 97 percent were satisfied with the knowledge they received about the genes tested, and 99.5 percent of participants felt their post-test genetic counseling was valuable to them. Those respondents also expressed an interest in receiving broader cancer screening in the future.

The study gave Emory doctors insight into extreme interest in genetic testing of cancer susceptibility genes in the community, and allowed them to see this program would allow achieving that testing at an accessible rate. The results of the study revealed that a remote-directed screening process could be just as effective as having in-person testing, and could deliver even more benefits if implemented correctly. Ultimately, access to a screening program such as JScreen might offer the ability to change the lives of many, not just in the Jewish community.

In a related study conducted by Emory University in 2018, also observing the effectiveness of JScreen, very similar results revealed satisfaction from both the participant and doctors performing the testing. “Making cancer genetic testing accessible is key,” said Dr. Jane Meisel, associate professor of hematology and medical oncology at the Emory University School of Medicine, and medical director of JScreen’s cancer program. “Testing through JScreen is important because it alerts people to their risks before they get cancer, allowing them to take action and prevent cancer altogether or to detect it at a treatable stage.”

Following testing through another JScreen study, knowledge quiz scores improved significantly and patient satisfaction was rated at over 98%, proving that a screening program like JScreen is effective and pleasing to the patients.

While these studies did provide participants with peace of mind that they were not carriers of the BRCA gene, the ultimate goal was to determine if a telehealth platform was effective in providing patients with genetic testing that was easily accessible and low cost, leading to greater participation. Many patients may not want to endure an abundance of doctor appointments to tell them if they are a carrier for cancer genes; this program showed effectiveness in providing patients with the results they needed without the hassle of appointments and long waiting periods. It created a higher participation rate.

Moreover, the study not only showed the effectiveness of the telehealth program overall, but but also demonstrated the possibility of success in the Jewish community specifically.

This has led researchers to forecast that this telehealth model for a cancer genetics program can be both effective and affordable to a target audience, giving many people peace of mind. The team is always working on new projects, Hardy says, which could lead other researchers to create similar programs, giving patients the genetic accessibility that they deserve and should have already had access to in the past.