News Team member Caroline Hansen reports that hospital closures across the United States threaten equitable healthcare access for rural populations and demand solutions.

The Promise of Multi-Cancer Early Detection Tests

A single test that can detect many cancers is a Holy Grail of research, but cost and regulation have slowed development til now.

By Min Ju Emily Kim

Cancer is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for 10 million lives in 2020. However, cancer mortality is reduced when detected and treated early. According to the New York State Cancer Services Program, cancer screening in the U.S. has helped lower cervical cancer death rates by more than 50 percent in the last 30 years.

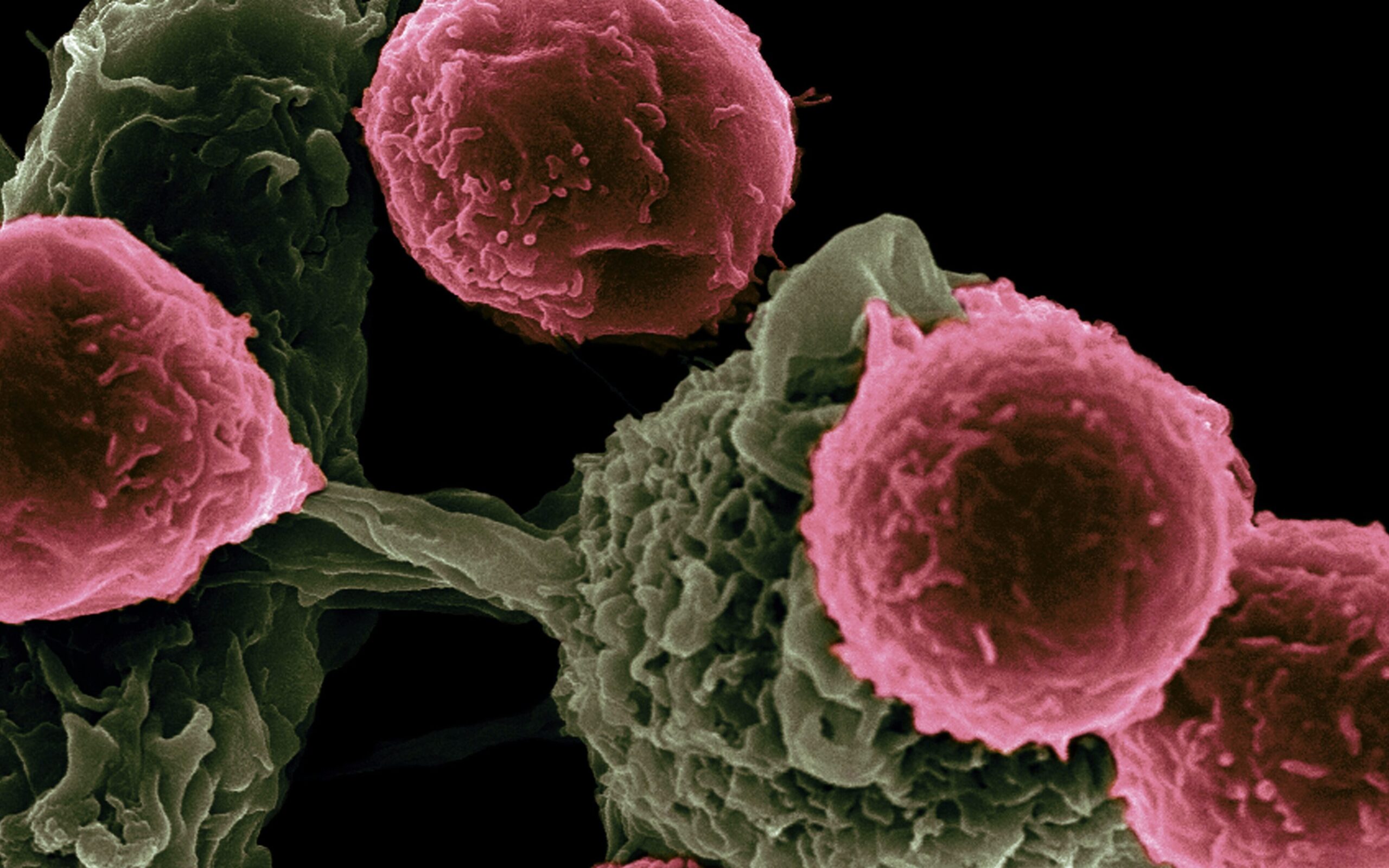

Currently, there are recommended screening tests for only five types of cancer: breast, cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate. For patients with more lethal cancers such as pancreatic cancer, the current market has no effective way of screening early. However, a new approach called the multi-cancer early detection (MCED) screening test has the potential to detect over 50 types of cancer. The MCED screening test detects cancer through cell-free DNA or other circulating analytes in the blood shed by tumors.

Last summer, researchers at the Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute of Cleveland Clinic evaluated the effectiveness of the MCED screening test, which detected a cancer signal within 4077 U.S. participants — 2823 cancer patients and 1254 non-cancer patients. The cancer status results were confirmed after a year, published in June 2021.

“Nearly 6,000 people die from cancer every year, so there’s this huge unmet need to screen for different types of cancers,” said Dr. Eric Klein, MD, Emeritus Professor and Chair Glickman Urological and Kidney Institute, “Most cancers we detect are on the surface: breast, prostate which you can feel with a finger, colon which you can look at with a scope, cervical which you can visualize directly.”

Dr. Eric Klein and his research team measured the overall sensitivity for cancer signal detection at 51.5 percent, and the overall percentage increased in proportion with later stages of cancer. Those with stage 4 cancer had 90.1 percent sensitivity, whereas those with stage 1 had 16.8 percent sensitivity on the screening test. The proportions of the positive test results for cancer patients and the negative test results among non-cancer participants were compared to test the MCED screening test’s overall sensitivity to cancer.

Also, the cancer signal origin, which is the MCED screening test’s ability to predict the location of the tumor, was 88.7 percent accurate in those that tested positive for cancer. In response to these overwhelming statistics, Dr. Eric Klein predicts, “It will be a part of our routine healthcare, a routine part of screening, and my guess is that it’ll be a blood test every year.”

However, the problem lies in the cost. GRAIL, a San Francisco biotech start-up, partnered with the UK NHS in releasing a MCED screening test called the Galleri Test on the market for $949[3]. The company released its final PATHFINDER study results, which indicated a 97.1 percent accuracy in predicting cancer signal origin in 6,662 individuals, in September 2022 at the European Society for Medical Oncology Congress in Paris. The Galleri Test is the only MCED screening test marketed without payer coverage and is currently not FDA-approved.

Other US companies such as Exact Sciences and Freenome are chasing FDA approval to compete with GRAIL. Adding to the anticipation, President Joe Biden’s Cancer Moonshot 2022 includes MCED screening test trials as a main priority for funding.

According to Joseph Lipscomb, Ph.D., a professor of health policy and management in the Rollins School of Public Health], “The MCED test will have to be at a reasonable cost. It isn’t currently but it will have a similar impact as the computer chip industry and the companies are working to improving the technology.” Lipscomb, who has published on decision modeling for MCED use, deployment of the tests will invoke a version of the famous Moore’s Law that predicted the increase in computational power of integrated circuits; in this case, the growth of cancer research will be exponential, and the cost will proportionally decrease.

As researchers conduct more clinical trials, the MCED screening test should become FDA-approved and readily available for the public at a low cost. Through our efforts to beat cancer, we may see a significant improvement in the history of cancer research.