News Team member Ananya Dash reports how severe flu infection can lead to neurological challenges in newborns and how annual flu vaccination can protect mothers and babies alike.

By: Dynasti deGouville

Over the past decade, social media has gained popularity at an unprecedented rate. In 2020, the worldwide number of social media users jumped to 3.81 billion people, an immense leap from the 2.07 billion social media users in 2015. This rise in social media popularity has proven to be both a beneficial and detrimental technological advancement. On one hand, it connects individuals to communities, helps people find love or their long lost sibling, and updates users on global news and methods of helping those in need. On the other hand, some studies have identified negative mental health effects of social media, linking excessive use to an increase in depression and anxiety in teens and young adults in particular.[1] While the conclusions of these studies often contradict, the general consensus is that young people are beginning to frequently use social media for everyday interactions.

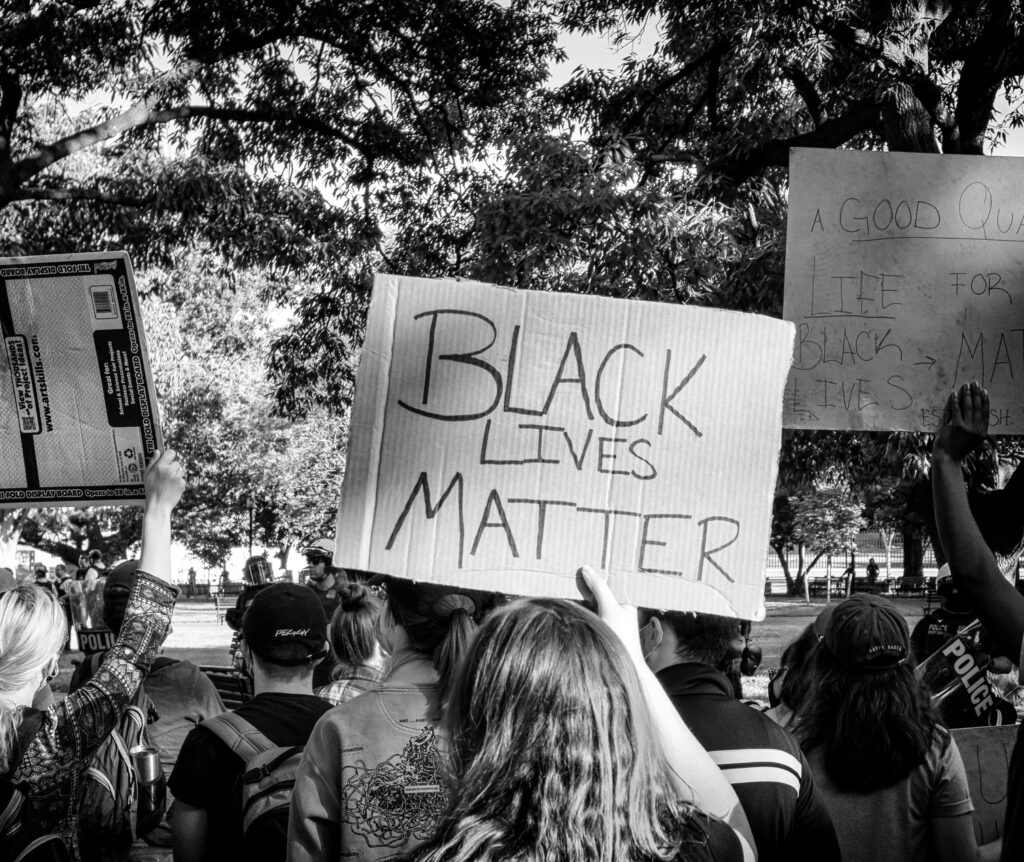

Recently, social media has been an integral tool in raising awareness for the Black Lives Matter movement. Although this attempt at raising awareness led to a resurgence in protests, it also led to an increase in circulation of ‘trauma porn.’ Trauma porn refers to the perverse infatuation people may have with the suffering and misfortune of others. The sharing of videos and images of emaciated children in a famine, refugees drowning off the Mediterranean shore, or fatal encounters between African Americans and the police are all examples of trauma porn. This term, by its own merits, denotes the obscenity of consuming trauma for one’s own pleasure by combining two words that we tend to avoid thinking of as associable by virtue. Although the circulation of trauma porn is defended under the guide of ‘raising awareness,’ most argue that shocking someone into action is not the only efficient way to get people to act. Whether or not one agrees, there is undeniable evidence that the hypervisibility of police brutality and racial profiling negatively affects the mental health of African Americans and plays a role in continuing legacies of trauma.

Mental Health Effects of Police Brutality

Public awareness of police killings of unarmed Black Americans has been galvanised by the high-profile deaths of Oscar Grant, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Walter Scott, Breonna Taylor, Freddie Gray, George Floyd, and Stephon Clark, among others. Black Americans are nearly three times more likely than are white Americans to be killed by police–accounting for more than 40% of victims of all police killings nationwide–and five times more likely than are white Americans to be killed unarmed. The trauma associated with witnessing police killings of Black Americans can be experienced vicariously, affecting those who may not even be directly associated with the murder victim. Police killings may compromise mental health among other Black Americans through various mechanisms including heightened perceptions of systemic racism and lack of fairness, loss of social status and self-regard, increased fear of victimisation and greater mortality expectations, increased vigilance, diminished trust in social institutions, reactions of anger, activation of prior traumas, and communal bereavement.[2]

The continuation of systemic racism has led Black communities to continue trauma responses over generations through DNA methylations and other DNA modification mechanisms[3], but how exactly does the hypervisibility of Black death on social media affect the severity of these stress responses? The witnessing of Black death on social media seems almost unavoidable. The sharing of Philando Castille’s shooting which was filmed and broadcasted on Facebook by his girlfriend was shared over 5 million times on Facebook alone, excluding any sharing and interactions on other social media platforms such as Twitter or Instagram.

“It’s upsetting and stressful for people of color to see these events unfolding… It can lead to depression, substance abuse and, in some cases, psychosis. Very often, it can contribute to health problems that are already common among African-Americans such as high blood pressure.”

-Monnica Williams, Center for Mental Health Disparities at University of Louisville

Scrolling through social media platforms days after the video of George Floyd’s death surfaced, the pain and anger were evident. Several users were commenting on the brutality of his death, the devastation of his loss, and the rage they felt at the sheer inconsideration for Black lives simultaneously. This is exhausting to most people. One user, six days after George Floyd’s murder, tweeted:

“Social media is emotionally exhausting and draining and triggering but I can’t physically drag myself away, is anyone else feeling like this?”

-@tiamarieart, Twitter

The responses to this tweet are overwhelmingly in agreement with over 10.9k retweets and 33.5k likes. Black Lives Matter activist Britney Packett recounts the moment she watched the video of Tamir Rice’s murder and the pain that accompanied it: “I saw the Tamir Rice video while sitting in the parking lot next to the park where he was killed. In hindsight, did I need to feel that pain watching the video in order to fully absorb what clearly was a tragedy? No. So why did I? Pressure.”[4] Indeed, the pressure activists feel to deliberately expose themselves to trauma porn is immense, and the resulting mental pain, the chest tightness, and the physical revulsion are all symptoms of the hypervisibility and consumption of Black death.

What Should We Do Moving Forward?

The first step is recognizing when enough is enough. April Reign, a former attorney and now managing editor for Broadway Black, says “recognize that if you’re numb, that means something. If you’re breaking down in tears, that means something… Understand it, and actively move toward healing yourself.”[4] While the task of healing may be daunting, the Association of Black Psychologists have released guidelines for how to properly care for yourself when we are experiencing racial stress or trauma:[5]

- Self-monitor for signs of stress and trauma. Be familiar with the signs of too much stress and get help or support. Accept that you may not be able to self-assess reactions and be open to feedback from others.

- Restore the well that is you. Take a break from social media and the news. It’s easy to succumb to the pressures of staying up-to-date, but it’s important to fill yourself with positive, comforting thoughts and experiences. Pace yourself between low and high-stress activities.

- Let others replenish the well. Ask for help. Seek out comfort and conversation with those who love and understand you.

- Stay spiritually grounded. This may include prayer and/or mindfulness. This is the time to connect with whatever higher power you believe in.

- Remember your body. Release energy, tension, and the strain to your body that comes from carrying stress and trauma. Walk, exercise, stretch, meditate– whatever best serves you, but do something physical. Remember to breathe deeply. Remember to relax your shoulders and your jaw. Feed yourself healthy food that brings energy and recharges the body. Avoid using alcohol, caffeine, or other substances to cope.

- Be intentionally kind and gentle with yourself and those around you. Laugh more. Practice random acts of kindness. Use positive self-talk and positive attitudes and talk to people you trust.

Change begins at the individual level, and if your mind, soul, and body are taxed and exhausted, you are not using your full potential. Take care of yourself.

References:

[1]Karim, F., Oyewande, A. A., Abdalla, L. F., Chaudhry Ehsanullah, R., & Khan, S. (2020). Social Media Use and Its Connection to Mental Health: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 12(6), e8627. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8627 [2]Bor, J., Venkataramani, A., Williams, D., Tsai, A. (2018). Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. The Lancet, S0140-6736(18)31130-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ [3]Yehuda, R., Lehrner, A. (2018). Intergenerational transmission of trauma effects: putative role of epigenetic mechanisms. World Psychiatry, 17(3): 243—257. doi: 10.1002/wps.20568. [4]Downs, Kenya. (2016). When black death goes viral, it can trigger PTSD-like trauma. Public Broadcasting Service. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/black-pain-gone-viral-racism-graphic-videos-can-create-ptsd-like-trauma [5]Association of Black Psychologist. (2016). Family-ÂCare, Community-ÂCare and SelfÂ-Care Tool Kit: Healing in the Face of Cultural Trauma. Community Healing Network. https://d3i6fh83elv35t.cloudfront.net/newshour/app/uploads/2016/07/07-20-16-EEC-Trauma-Response-Community-and-SelfCare-TookKit-1.pdf